Science Is Not Personal

Civilians often make the mistake of believing that science is personal. They are wrong on at least two accounts.

First, civilians believe that every single conclusion about certain categories of humans apply to them individually and personally. One of my scientific heroes, the Northwestern behavior geneticist J. Michael Bailey, expresses it best when he comments on my past controversy:

I can understand why black women would be upset by his contention that on average they are less attractive. Their reaction may be human nature, but it is not rational. Why should I care about the alleged attributes of my race? (My attributes are my attributes, no matter what race I am. My IQ is my IQ; my attractiveness is my attractiveness, etc.)

One

important point which Bailey’s comment above elucidates is the fact

that, at the current historical stage, biological and behavioral

sciences are not as advanced as physical sciences. We do not have

invariant laws in biological and behavioral sciences (with the possible

exception of the law of evolution), and all scientific conclusions in

biological and behavioral sciences are empirical generalizations.

Even when completely accurate and correct, empirical generalizations

always have exceptions, because the traits in question have nontrivial

variances around their means. In other words, as Bailey points

out, not all scientific conclusions in biological and behavioal sciences

apply to all individuals equally accurately, so there is no need for

any individual to take any empirical generalization about their sex,

race, culture, class, etc., personally.

One

important point which Bailey’s comment above elucidates is the fact

that, at the current historical stage, biological and behavioral

sciences are not as advanced as physical sciences. We do not have

invariant laws in biological and behavioral sciences (with the possible

exception of the law of evolution), and all scientific conclusions in

biological and behavioral sciences are empirical generalizations.

Even when completely accurate and correct, empirical generalizations

always have exceptions, because the traits in question have nontrivial

variances around their means. In other words, as Bailey points

out, not all scientific conclusions in biological and behavioal sciences

apply to all individuals equally accurately, so there is no need for

any individual to take any empirical generalization about their sex,

race, culture, class, etc., personally.

This would be different in physical sciences. If you are a photon, and if a particle physicist says something racist like “Photons are massless,” then, yes, you should take it personally, because he is saying that you, personally, and every other photon in the universe, are massless. Few observations in biological and behavioral sciences could be that precise and accurate, at least for the foreseeable future. Taking scientific conclusions based on broad empirical generalizations personally, as if they apply to every single person in the category equally, is the first way in which civilians misunderstand science as personal.

Second,

civilians believe that scientists are motivated to conduct scientific

research, and, more importantly, reach certain scientific conclusions,

for personal reasons. Another scientific hero of mine, the

SUNY–Albany evolutionary psychologist Gordon G. Gallup, Jr., expresses it best when he comments on civilian reactions to some of his own controversial theories:

Second,

civilians believe that scientists are motivated to conduct scientific

research, and, more importantly, reach certain scientific conclusions,

for personal reasons. Another scientific hero of mine, the

SUNY–Albany evolutionary psychologist Gordon G. Gallup, Jr., expresses it best when he comments on civilian reactions to some of his own controversial theories:

A lot of people think that if a person has a theory it’s a window into their soul. I have lots of theories. I have a theory of homophobia, I have a theory of homosexuality, and I have a theory of permanent breast enlargement in women, just to mention a few. So that would make me a homophobic homosexual who is preoccupied with women’s breasts. I am not homophobic and I’m not homosexual. My only interest in homosexuality and homophobia is to use evolutionary theory to generate evidence that may shed new light on what have heretofore been poorly understood phenomena.

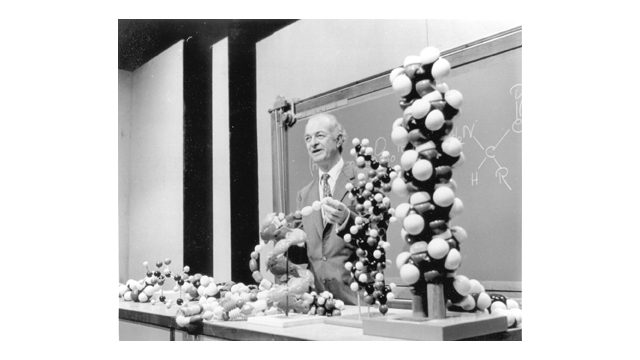

When I discovered some race differences in physical attractiveness, my critics automatically assumed that I must hate black women, or I must have been rejected by a black woman. Such assumptions belie fundamental misunderstanding of the scientific process. I don’t hate black women any more than Watson and Crick hated the triple helix – an alternative structure for the DNA seriously proposed and advanced for a time by the Nobel prizewinning chemist Linus Pauling.

The conclusions that scientists reach reflect the underlying nature, the scientists’ best interpretation of how the world works. It has nothing to do with the scientists themselves. As Gallup – one of the most prolific and creative scientists in the past half century – points out, it’s not “a window into their soul.” Believing that scientific conclusions must reflect the personal opinions of the scientists, as if they are unconstrained by nature, is the second way in which civilians misunderstand science as personal.

Science is not personal. It’s a deeply impersonal, cold, and detached process of accumulating more and more useless and boring knowledge purely for its own sake.

Follow me on Twitter: @SatoshiKanazawa