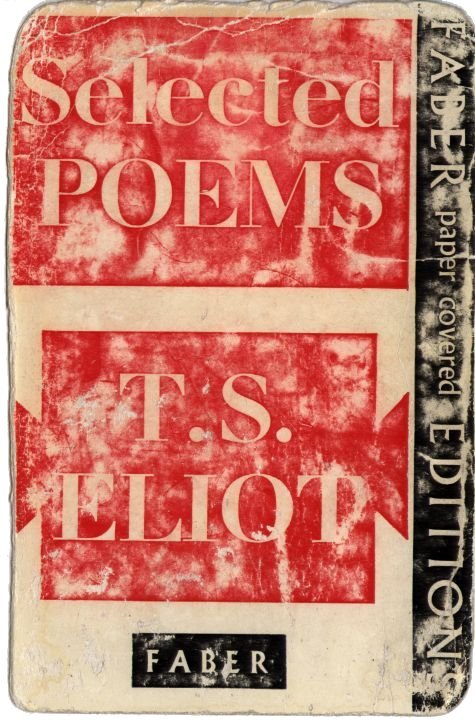

That’s the cover of an old book I’ve carried around in coat pockets over a number of years. It took me a long time to “get” any poetry, but reading this book over and over again finally did it. I believe in the power of repetition; I suspect the reason most people start liking the lyrics in their favourite popular music is that they hear them hundreds of times. With repetition comes memory and a personal emotional connection, and only after that comes appreciation (more often than not of one’s own emotions, not the words in the song).

When this happens, it becomes difficult to tell what you’re reading anymore: is it the poem or all the things you’ve projected on it? Later on I’ve liked some poems on the first reading, and in those cases it doesn’t seem so unreasonable to think you’re “actually” understanding the poem. Now I want to try to think a bit more carefully about the ones I already like, to undo some of my previous distortions, if you will.

This is the inside of the cover:

I also happen to believe in cheap, small books of poems. Contemporary volumes are quite nicely made and go for around 20€; they should be as cheap as possible for easy experimentation, borrowing, getting scuffed being carried everywhere etc. The price of this book, 5 shillings in 1967, is about £7.30 in 2005 pounds. I like the print and simple typesetting better than that of 2005 books.

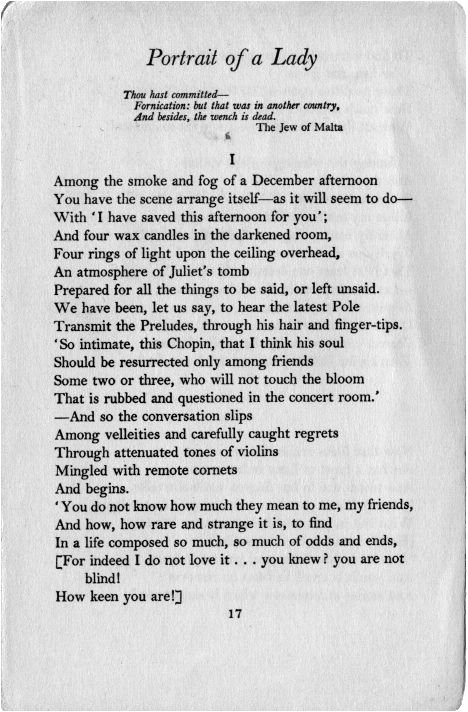

The opening quotation is from a 16th century play by Christopher Marlowe. The quotation features the main character, Barabas, dismissing Christian aspersions on his character.

FRIAR BARNARDINE. Barabas, thou hast–

FRIAR JACOMO. Ay, that thou hast–

BARABAS. True, I have money; what though I have?

FRIAR BARNARDINE. Thou art a–

FRIAR JACOMO. Ay, that thou art, a–

BARABAS. What needs all this? I know I am a Jew.

FRIAR BARNARDINE. Thy daughter–

FRIAR JACOMO. Ay, thy daughter–

BARABAS. O, speak not of her! then I die with grief. [Barabas poisoned her for becoming a nun]

FRIAR BARNARDINE. Remember that–

FRIAR JACOMO. Ay, remember that–

BARABAS. I must needs say that I have been a great usurer.

FRIAR BARNARDINE. Thou hast committed–

BARABAS. Fornication: but that was in another country;

And besides, the wench is dead.

It’s sometimes said that Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice might be too anti-semitic for performance; this one is perhaps only saved by its lesser fame.

The poem describes a person with a particular kind of social dominance, a perpetual sense of injury and outsidedness. Barabas similarily imposes his downtrodden Jewishness on others, although in an altogether meaner manner than the lady of the poem. An indelicate comparison considering what follows.

You have the scene arrange itself – as it will seem to do – a person you subconsciously suspect of some manipulation; someone you’re supposed to like and do like in some sense, but can’t help but be ill at ease with. There’s a pre-conversation marking you as a friend who will not touch the bloom, “I don’t care about my life, but only for my inoffensive friends…”

A velleity is a limp wish or desire, with no effort to fulfil it. Velleities and carefully caught regrets; were that it were so, why must we be thus. These compose about half of my conversations.

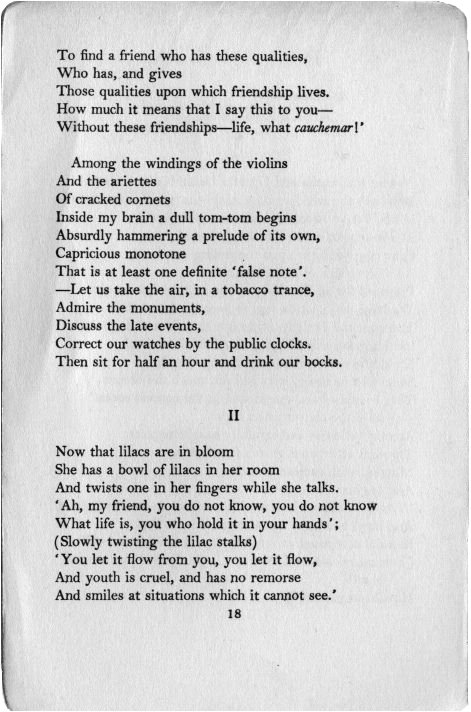

How much it means that I say this to you – such statements seem to me to land with a hollow thud; it’s weighty, but you’re not sure how true it is (even if you want to believe it) if only because usually when something means a lot, nobody needs to point it out.

Cauchemar is French for nightmare.

Inside my head a dull tom-tom begins — That is at least one definite “false note”. One always feels out of place with people who seem too much “in place”. The lady is palely setting out what great meaning things have to her, but you’re not quite sure, feeling like you should be; uncomfortable, guilty.

Eliot later wrote a much more famous poem, The Waste Land, the opening of which mentions lilacs. I can’t help thinking of that violent scene at the mention of lilacs here:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

So, she is older? Old, full of regrets, unhappy, bitterly smiling at the cruelty of youth (the cruelty of it to exist).

But immediately to contradict this, I feel immeasurably at peace. And to top off the confusing jumble the insistent out-of-tune voice says I am always sure you understand / My feelings, always sure that you feel

There is no defence (apart from the smile) to this art of making someone feel they’re altogether the wrong kind of person. The need to make amends to what has been said to you: I’ve often known that.

I don’t know why things that other people have desired damages the speaker’s countenance. Perhaps it’s the idea of a more real life in contrast to the atmosphere of Juliet’s tomb.

I very much like the mounted on my hands and knees -turn of phrase. Ill at ease / hands and knees. It also makes me think of the stairs in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock:

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair

The You hardly know when you are coming back part evokes to me (I apologise if this is getting tedious) a Bob Dylan song, Boots of Spanish Leather:

I got a letter on a lonesome day,

It was from her ship a-sailin’,

Saying I don’t know when I’ll be comin’ back again,

It depends on how I’m a-feelin’.Well, if you, my love, must think that-a-way,

I’m sure your mind is roamin’.

I’m sure your heart is not with me,

But with the country to where you’re goin’.

Now the lady, contradicting herself again, wonders “Why we have not developed into friends“, making the speaker even more self-conscious, like someone displeased at catching the reflection of his own expression.

I like the use of “gutter” as a verb.

The pressure now, the pressure to please, to avoid injury, to make good at least in part on these expectations.

The next thought seems to arrive when the scene has already been escaped: What if she should die some afternoon — leave me sitting pen in hand — Doubtful, for a while / Not knowing what to feel or if I understand — Would she not have the advantage, after all? But we come back to the Chopin, and an uneasy conclusion.

These earlier Eliot poems often have these themes of being somehow intimidated by the world, often trembling in some unmentionable passion, communicating about the inability to communicate. Later on there’s a level, sometimes grandiose illustrative vein, and towards the end a kind of collapsing disappointment and sadness with the world. The first kind, this sensation of having your mind pushed around against your will, is the most familiar to me now.