Yleensä kun tapaan jonkun pitkästä aikaa ja keskustelemme jostain, hän huomaa minun muuttuneen.

“Etkö sinä aiemmin ajatellut tästä ihan päinvastoin?”

“No joo, tai itse asiassa taustalla olevat periaatteethan ovat samat, mutta…”

Takinkääntämisen tunnustaminen on kiusallista. Kantani ovat muuttuneet, joissain asioissa totaalisesti, ja koen tarvetta selitellä tätä parhain päin. Haluan muodostaa ajattelustani loogisen jatkumon enkä näyttäytyä tunteiden ja elinolosuhteiden heittelemänä kevytajattelijana.

Tosiasiassa en ole aina itsekään enää varma mitä olen milloinkin ajatellut tai miksi olen muuttanut mieltäni. Ajattelussa on tiettyjä polkuriippuvuuksia. Mennyt minä vaikuttaa nykyiseen minääni, vaikka nykyisen minän on vaikea enää kunnolla ymmärtää entistä minääni.

Ulkopuolisen silmin ihminen on ennen kaikkea ympäristönsä ja elämänvaiheidensa tulosta. Muutokset johtuvat iän tuomasta kokemuksesta, vaurastumisesta tai köyhtymisestä, yksinäisyydestä tai sosiaalisuudesta, perheen perustamisesta tai sen tekemättä jättämisestä. Sisäisesti kukin muistaa ajatuskulkunsa, tärkeät keskustelut ja lukemansa kirjat jotka ovat muokanneet omaa ajattelua. Itselleni se “oikea tarina” on tietenkin sisäinen, älyllinen polkuni, mutta rehellisyyden nimissä yritän myös mainita relevantteja elämäntapahtumia. Totuus on varmaankin jotain siltä väliltä.

Hyödyllisenä harjoituksena ja tulevana viittauskohteena (“jos juttelimme viimeksi lukiossa, käy lukemassa täältä mitä sen jälkeen tapahtui”) koostan tähän jotain kehitysvaiheita. Saatan päivittää kirjoitusta kun uusia muistuu mieleen, tai aikaa kuluu tarpeeksi että olen taas muuttanut mieleni kaikesta.

Lapsuus

Lapsena on täysi työ omaksua yleistietoa ja elämänmenoa, ja vain hyvin harva on niin pikkuvanha, että asettuu ala-asteikäisenä jollekin omintakeiselle poliittiselle kannalle. Itse muistan oppineeni politiikasta lähinnä sen, että Keskusta on puolueista ketkuin ja Paavo Väyrynen ketkuista ketkuin. Tv-uutisista mieleen jäi poliittisia persoonallisuuksia, tyyliin Martti Ahtisaari ja Elisabeth Rehn. Kunnioitusta ei päättäjiä kohtaan tunnettu, ja minuunkin he tekivät huonomman vaikutelman kuin esimerkiksi omat vanhempani.

Päättäjien sijaan aloin pitää arvossa kirjailijoita ja toimittajia. Toimittajathan arvostelevat kaikkia muita, mukaanlukien poliitikkoja ja yritysjohtajia, ja nämä arvostelun kohteetkin lukevat, mitä toimittajat kirjoittavat. Toimittajat kirjoittavat myös kaikesta taivaan alla, mikä on omiaan antamaan sellaisen vaikutelman että he tietävät paljon ja ovat kaikkien kunnioittamia.

Ala-asteella oli tuolloin jo elämänkatsomustiedon opetusta vaihtoehtona uskonnon tunneille, mutta mitään varsinaista opetusta ei yleensä ollut, vaan lapsille näytettiin piirrettyjä tai puuhailimme mitä sattui. Pidin kuitenkin et-tunneilla olemista järkevyyden merkkinä, ja taisin olla myös hieman tuohtunut uskonnollisista aamunavauksista joita keskusradiossa joskus lähetettiin.

Mieleeni on kuitenkin jäänyt ala-asteelta filosofiapäivä (vai oliko se yleisemmin tiedepäivä?) jota varten tehtiin julisteita ja esityksiä. Tämä oli rehtori Ilkka Olkkosen (jonka huomaan olevan yhä edelleen Ahmatien ala-asteen rehtori) keksintö, ja hän pyysi ehdotuksia päivää varten. Olin saanut jostain erinomaisen “for Beginners” -kirjasarjan osan Philosophy for Beginners, ja esittelin ja lainasin tätä teosta. Sieltä löysi tiensä johonkin pieneen monivalintatehtävään kysymys Francis Baconin kokeesta, jossa hän pyrki osoittamaan yhteyden lihan pilaantumisen ja lämpötilan välillä (1600-luvun alussa). Tämä oli minusta ilahduttavaa, ja innostuin filosofiasta pitkäksi aikaa. Tuolloin filosofia merkitsi minulle ennen kaikkea empirismin ja luonnontieteiden perusteita (sen lisäksi että se on jotain jota arvostetut, tärkeänoloiset miehet tekivät). Philosophy for Beginners -kirjassa Descartesin dualismi ja “Ajattelen, siis olen” olivat merkittävässä osassa. Pidin niitä tuolloin melko typerinä pohdintoina.

Yläaste

Yläaste oli enimmäkseen masentavaa aikaa. Keskityin selviytymiseen, mutta kai siellä jotain tapahtuikin.

Ateismini tuli entistä julistavammaksi, ja muistelen nyttemmin häpeällä, miten yritin jatkuvasti vetää koulun (harvoja) uskovaisia mukaan väittelyihin joissa jankkasin uskontojen typeryydestä.

En ole varma tarkalleen mistä, mutta jostain olin tähän ikään mennessä omaksunut myös tyypillisiä kantoja liittyen mm. amerikkalaisiin (yksinkertaisia), aborttiin (hyvä asia jota uskovaiset vastustavat) ja aseisiin (huono asia jota amerikkalaiset kannattavat). En tarkoita kritisoida näitä kantoja – ne ovat kaltaisilleni ihmisille äidinmaitoa – haluan vain todeta että tässä vaiheessa tulin niistä tietoiseksi.

Aloin tutustua enemmän politiikkaan, ja päädyin ilman kummempia harhapolkuja vasemmistolaiseksi. Minuun teki aluksi vaikutuksen erityisesti työn ja pääoman ristiriita (miksi vain osa työn tuloksista päätyy työn tekijälle, joka on välttämätön, ja loput pääoman omistajalle joka voisi olla kuka tahansa?) ja köyhien puolustaminen. Pohdin pääoman kasautumisen ongelmia ja rajoja, ja erityisesti maanomistus huolestutti minua (jos pieni omistajajoukko omistaa kaiken maan, eikö heistä voi tulla de facto diktaattoreja?).

Toisin sanoen pelkäsin kontrolloimatonta epäoikeudenmukaisuutta ja dominanssia (tai: alistusta, riistoa), ja näin vasemmistolaisuuden puolustuskeinona näitä vastaan.

Aivan yläasteen loppupuolella ehdin perehtyä myös marxismin teoriaan. Tutustuin sellaisiin käsitteisiin kuin dialektinen materialismi, mitä en ymmärtänyt, mutta tajusin kuitenkin mitä filosofit tarkoittivat materialismilla. Historian “vääjäämätön kehityskulku” ei vakuuttanut minua, vaan olin pikemmin pessimistinen kommunismin saavuttamisen suhteen, vaikka se vaikuttikin mielestäni ihanteelliselta.

Tuolloin, vuoden 1998 tienoilla, sosialistiset ihanteet tuntuivat marginaalisilta mutta jalon oikeamielisiltä, ja tiesin että monet akateemiset henkilöt kannattivat niitä. Vuonna 1999 oli “Seattlen sota”, WTO:n vastainen suuri mielenosoitus, ja olinkin siitä jotenkin tietoinen, mutta jostain syystä en assosioinut sitä mielessäni omaan sosialistiseen ajatteluuni, vaan enemmän sellaisiin asioihin kuin Rage Against The Machinen kuuntelemiseen ja turkistarhaiskuihin. Itse olin enemmän nörtti, ja tuossa iässä tällaisilla ulkoisilla seikoilla oli paljon merkitystä.

Lukio

Lukiossa tutustuin ensimmäistä kertaa muihin ikäisiini joita kiinnosti politiikka. Siitä keskusteltiin paljon, tosin ei niinkään aiemmin mainituilla (vasemmisto)teoreettisilla linjoilla, vaan konkreettisemmin milloin mistäkin. Suuri enemmistö ystäväpiiristäni oli vasemmistolaista, joten suurilla linjoilla kipinät eivät lentäneet. Ei-vasemmistolaisiakin oli, mutta heitä ei yleensä kiinnostanut ruveta väittelemään asiasta.

Internet alkoi merkitä yhä enemmän, ja sain IRC:n välityksellä läheisemmän yhteyden erilaisiin poliittisiin näkökantoihin viettämällä aikaa #politiikka-kanavalla. Muistan erityisesti väsymättömät libertarismin kannattajat, joiden maailmankuvan eheää loogisuutta ei voinut olla ihailematta. Tunsin siihen jonkinlaista vetoa, mutta lopulta pysyin sosialistina. Muistan erityisesti, että monet keskustelut päätyivät libertaristin argumenttiin “Jos sosialistinen ratkaisu tähän poliittiseen kysymykseen on niin hyvä, mikset tyydy muiden vasemmistolaisten kanssa verottamaan toisianne ja ylläpitämään sitä ratkaisua, jolloin voisitte jättää rauhaan ne jotka eivät sitä halua?” En keksinyt tähän muuta vastausta, kuin että koordinaatio- ja julkishyödykeongelmat olisivat näissä olosuhteissa mahdottomia ratkaista. Ajattelin myös, että mahdollisesti velvollisuuteni on olla pakottamatta muita, ja kehittää vapaaehtoista sosialismia – tai vaihtoehtoisesti odottaa sitä päivää että kaikki muutkin haluavat sosialismia. Luovuin kuitenkin lopulta tästä ajatuksesta. Tutustuin myös IRC:n kautta vasemmistonuoriin ja nuoriin vasemmistoliittolaisiin, mistä lisää jäljempänä.

Se vaikutus tällä (tai jollain muulla, en ole varma millä) kuitenkin oli, että päädyin hyväksymään sen, ettei suunnitelmataloudesta voisi tulla mitään. Muutuin tässä vaiheessa marxisti-leninististä sosialistisen markkinatalouden kannattajaksi, vaikka olin tietoinen etten tiennyt miten sellaisen järjestelmän pitäisi toimia.

Filosofian ja elämänkatsomustiedon opettaja Juha Savolainen teki lähtemättömän vaikutuksen minuun ja moniin muihin oppilaisiinsa. Hän onnistui hyvään sokraattiseen tyyliin salaamaan oman näkemyksensä niin filosofisista kuin aatteellisistakin kysymyksistä, ja vastasi kaikkeen antamalla toisaalta-toisaalta -yleiskatsauksen. Erään ET:n kurssin aiheena oli “kuinka puhua mistä tahansa tietämättä aiheesta mitään”. Vilkkaimmat keskustelut käytiin metafysiikasta (vakuutuin kausaalisten selitysten tärkeydestä) ja etiikan teorioista. Muistan olleeni taipuvainen utilitarismin suuntaan, vaikkakin siihen liitetyt kritiikit vaikuttivat minusta mahdottomilta ratkaista. (Nykyäänkin pidän oikeastaan kaikkia etiikan teorioita hyvin ongelmallisina.)

Kiinnostuin suuresti Wittgensteinista ja Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus -teoksesta. Olen edelleen sitä mieltä, että siinä esitelty tapa käsitellä filosofisia ongelmia on erittäin valaiseva, ja että maailmassa olisi paljon vähemmän turhaa lätinää jos se olisi kaikilla kirkkaana mielessä.

Lukiossa ilmestyi Agitaattori-niminen vasemmistohenkinen julkaisu, johon kirjoittelin pohdintoja mm. siitä, voiko markkinataloudessa elävä hyvätuloinen henkilö olla sosialisti (kyllä) ja roskalehtien moraalittomuudesta.

Aika muodostaa kanta asevelvollisuudesta lähestyi, ja päädyin olemaan aatteellinen pasifisti. Ajattelin, että koska sotien ehdoton edellytys on se, että on armeijoita, jokaisen ihmisen moraalinen velvollisuus on olla liittymättä mihinkään armeijaan. Menin siviilipalvelukseen sillä perusteella, että vankila olisi varmaa haaskausta, ja haaskaus on väärin.

Muistan ajatelleeni että kolme positiota joista en varmaankaan koskaan tulisi luopumaan olivat pasifismi, sosialismi ja ateismi.

18-20

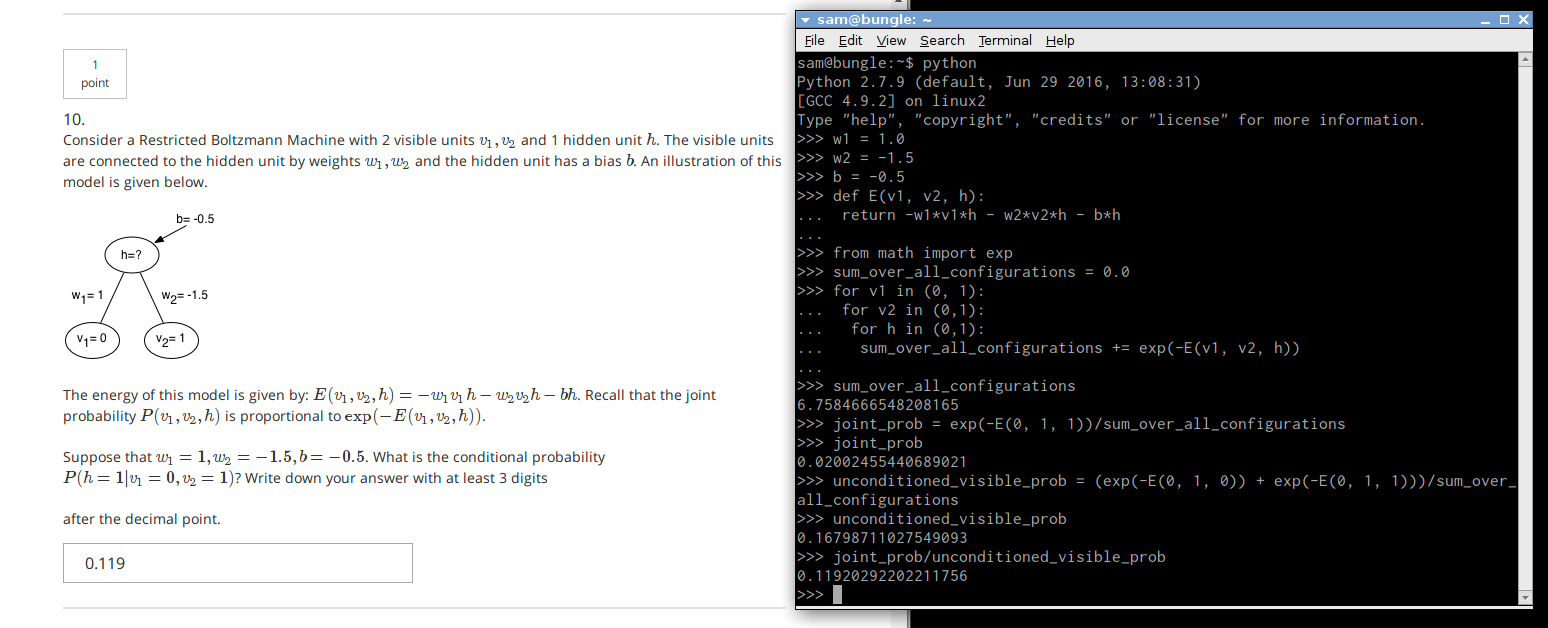

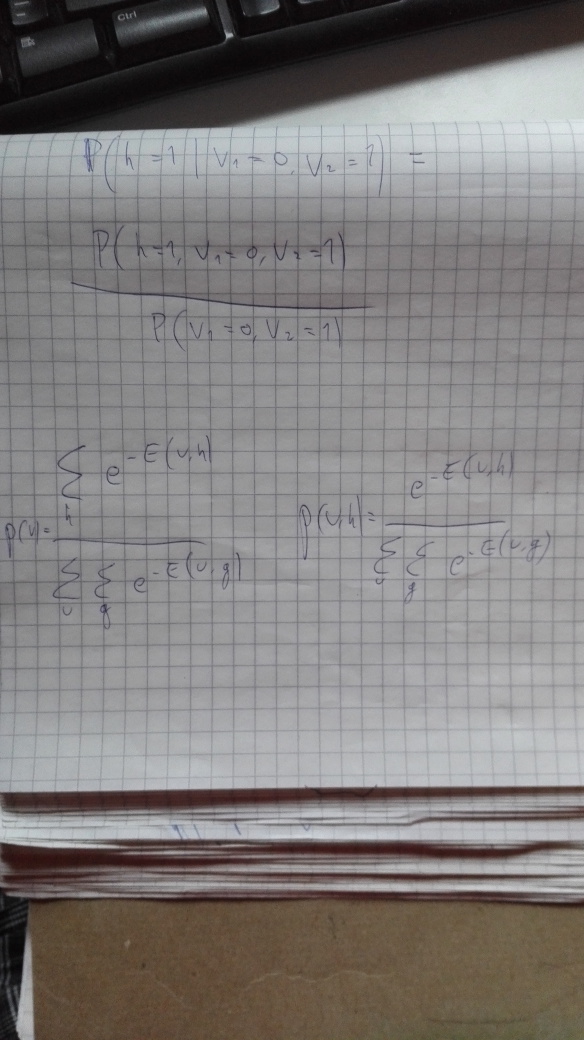

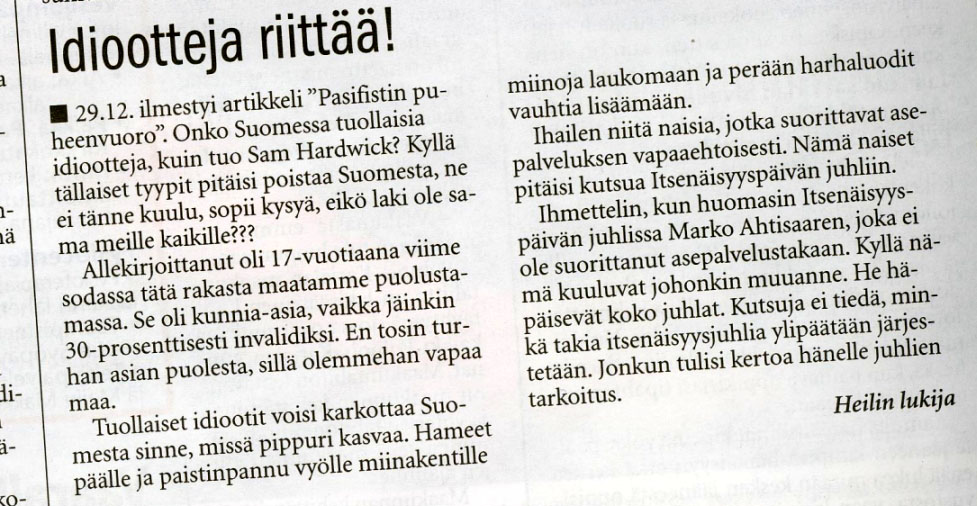

Siviilipalvelusmies Helsingistä oli ilmeisesti sellainen ilmestys että minusta tehtiin juttu Joensuun paikallislehteen Karjalan Heiliin, minkä kirvoittaman lukijapalautteen panin talteen:

Liityin Vasemmistoliittoon ja Vasemmistonuoriin. Olin IRC:n kautta tutustunut tähän porukkaan jonkin verran, ja nyt myös oikeassa elämässä. En ollut Vasemmistoliitosta puolueena loputtoman innostunut. Se oli liian laimea ja ponneton – puheenjohtajana oli Suvi-Anne Siimes, joka myöhemmin osoittautui vähemmän kuin tulenpalavaksi sosialistiksi. Ajattelin kuitenkin, että kun poliittinen järjestelmä on olemassa, siihen on velvollisuus osallistua.

Vasemmistonuoret olivat sydämellistä väkeä, joskin ei-niin-vakavamielistä (minkä tässä asiassa luin haitaksi) ja impulsiivista. Minua myös häiritsi tietty “järjestelmänvastaisuus” (esim. tahallinen sosiaalituen väärinkäyttö, kaiken rahan pitäminen käteisenä jotta sossu ei päässyt siitä vihille, vaikka ylimääräinen olisi mennyt kaljaan ja pilveen), joka ei ollut niissä porukoissa mitenkään universaalia, mutta kuitenkin suvaittua.

Sydämellisyys toki koski vain “omia”, mutta en joutunut kohtaamaan tämän asian varjopuolia.

Sosialistinen aate pysyi vahvana ja jopa voimistui. Yritin sovittaa yhteen ajatusta sosialistisesta markkinataloudesta ja pääoman kuulumisesta valtiolle. En halunnut tinkiä siitä, että yksityisestä omaisuudesta pitäisi päästä eroon. Tutustuin anarkosyndikalismiin, ja pidin erityisen lupaavana sitä, kun luin että Noam Chomsky kannattaa anarkosyndikalismin sitä periaatetta, että kunkin tuotantolaitoksen työläiset omistaisivat tuotteet ja päättäisivät tuotantoon liittyvistä asioista. En kuitenkaan vakuuttunut tästä. Se vaikutti ratkaisulta, joka voisi toimia vain joissain tietyissä teollisissa konteksteissa.

Näihin aikoin puhuttiin julkisuudessa “pareconista” (participatory economics), jossa oli tätä samaa ajatusta, mutta en jostain syystä vakuuttunut siitäkään. En myöskään innostunut ATTACista joka tuli Suomeen joitain vuosia aiemmin. Kaiken kaikkiaan olin jokseenkin nurkkakuntainen ajattelussani, kansainvälistä ulottuvuutta ei juuri ollut. Tähän vaikutti introverttitaipumukseni. Olin aikanaan muuttanut viime hetkellä mieleni Prometheus-leirille menemisestä, ja siellä olisi tutustunut monenlaisiin ihmisiin. Samoin olin viime hetkellä jäänyt pois Euroopan Nuorten parlamentista johon lukiomme joukkue oli saanut osallistumisoikeuden.

Menetin kiinnostukseni puhtaaseen filosofiaan ainakin siinä muodossa, kuin se yliopistokontekstissa esiintyy. Lukemani filosofiset artikkelit olivat täynnä epämääräisen oloista kieltä ja sisäänpäinkääntynyttä viittailua muihin filosofeihin, ja itse asiaan ei tunnuttu pääsevän. Pahimmassa tapauksessa itse asia oli pelkkää metatasoa, tyyliin “Onko digitaalinen kuva notationaalinen representaatio vai ei?” (tämä esimerkki tuli ensimmäisenä vastaan kun kokeilin etsiä Googlella viimeaikaisia filosofisia artikkeleja). Myöhemmin olen jossain määrin muuttanut mieleni tästä uudelleen, ja tunnustan, että maailmassa on paljon mielenkiintoista ja palkitsevaa filosofista tekstiä, mutta en kuitenkaan ole ollenkaan pahoillani siitä, etten ole akateeminen filosofi.

20-22

Aloin menettää uskoani sosialismin toteutumisen lisäksi siihen, että jos se toteutuisi, tuloksena voisi olla mitään hyvää. Aloin hyväksyä, että sosialismi on niin herkkää epäharmonialle ja erimielisyydelle, että se voisi toteutua lähinnä samanmielisten perustamassa ideaaliyhteisössä, mutta tällaisten yhteisöjen historiaan tutustuminen oli lannistavaa. Tähän asti minua oli vaivannut enimmäkseen pettymys ihmisiin sellaisina kun he elävässä poliittisessa elämässä olivat, nyt aloin pelätä ettei heitä voisi olennaisesti paremmalla korvatakaan. Niin noloa kuin se nyt onkin myöntää, olin käytännössä uskonut, että jos minä ja ystäväni saisimme päättää kaikesta, asiat olisivat paljon paremmin.

Olin tässä vaiheessa vielä sosialisti, mutta hyvin abstraktissa mielessä, vähän samaan tapaan kuin uskonsa menettänyt kristitty saattaisi vielä haaveilla taivaasta.

Menin yhteen tulevan vaimoni kanssa. Hyvän aikaa yhteiseen kotiimme tuli sekä Vasemmistonuorten että Kokoomusnuorten jäsenpostia.

Olin tähän asti lukenut paljon kaunokirjallisuutta, mutta nyt se alkoi vähetä selvästi. Seurasin nyt yhä enemmän Internetissä aktivoitunutta blogimaailmaa. (Olen jatkanut samalla tiellä tähän päivään asti. Vuonna 2015 olen lukenut yli 5000 blogikirjoitusta ja aikamoisen määrän blogikommentteja.) Luin myös lahjatilauksina saamia lehtiä kuten Prospect ja The London Review of Books, ja koin näiden julkaisujen sivistyneen, humaanin, kosmopoliittisen ja vasemmistolaisen maailmankuvan omakseni.

22-24

Tänä aikana lakkasin pitämästä itseäni sosialistina ja erosin Vasemmistoliitosta ja Vasemmistonuorista. Tähän liittyi yleisempi uskonmenetys ihmisjärkeen ja sen kehittämien järjestelmien toimivuuteen. Siinä, missä olin aiemmin huolissani siitä mahdollisuudesta, että taloudellinen valta voi alistaa ihmisiä, aloin kiinnittää yhä enemmän huomiota poliittisen vallan potentiaaliin alistaa ihmisiä.

Katsoin edelleen hyvällä esimerkiksi ammattiyhdistysliikkeiden saavutuksia ja vähempiosaisten auttamista, mutta näihin ilmiöihin alkoi nähdäkseni ajan kuluessa liittyä aina jotain ongelmia. Nykyään ehkä käyttäisin ilmausta diminishing returns – mitä enemmän jotain tehdään, sitä suurempi osa hyvistä vaikutuksista on saatu, ja niiden saavuttamiseksi luodut organisaatiot alkavat luutua ja ylläpitää itseään. Saavutettuaan valtaa ne alkavat potkia heikompia päähän siinä missä muutkin. Ay-liike Suomessa on tästä hyvä esimerkki. Minuun teki vaikutuksen esimerkiksi Matti Pulkkisen kirja Romaanihenkilön Kuolema, joka asetti kehitysavun erittäin arveluttavaan valoon. Olin aina ajatellut että kehitysapu nyt ainakin on hyvä asia, joten tämä oli kohtalaisen suuri pettymys.

En ollut tuolloin perehtynyt julkisen valinnan teoriaan, mutta mielessäni oli juurikin tuon taloustieteen alan tutkimia ongelmia. Siirryin monessa asiassa liberaaliin tai jopa libertaristiseen suuntaan.

Pitkäaikainen kehityskulku, joka tapahtui paljolti näinä vuosina, mutta oli saattanut alkaa jo hieman aiemmin, oli ihmiskuvani muuttuminen. Jälkeenpäin ajateltuna en tainnut edes ymmärtää, että minulla oli jokin ihmiskuva, enkä tiedä miten olisin sitä pyytäessä kuvaillut. Nykyään kutsuisin sitä sosiaalidemokraattiseksi tai yleishumanistiseksi ihmiskuvaksi, jonka keskiössä on universalismi – kaikkien ihmisten yhtäläinen ja jakamaton ihmisyys, ja (ehkä julkilausumaton) usko siihen, että jokainen ihminen on järjellinen ja hyvä, ja jos voisimme vain kaikki keskustella yhdessä ja ymmärtää toisiamme, maailma voisi olla harmoninen ja rauhallinen paikka. Tähän kuului myös sukupuolten ja etnisten ryhmien yhtäläisyys: sukupuolilla on vain pinnallisia eroja, ja miesten suurempi palkka kertoo historiallisesta alistuksesta ja sukupuolisyrjinnästä; rotuja ei ole olemassa; ihmiset ovat pohjimmiltaan samankaltaisia. Viime aikoina tästä ajattelutavasta on käytetty termiä blank slatism, ehkä Steven Pinkerin kirjan The Blank Slate mukaan. Luin tuon kirjan muistaakseni vähän aiemmin. Ehkä se jätti jonkin idun mieleeni.

Oli erittäin pitkällinen prosessi irtautua tästä, ja kapinoin sitä vastaan. Luin ahmien tämän ihmiskuvani vastaista kirjallisuutta, ensin halveksuen, mutta lopulta muutuin itse perinpohjin. Minulle oli suuri järkytys havaita, ettei tällä ihmiskuvalla ollut mitään tieteellistä pohjaa, ja että implisiittisesti lähes kaikkialta omaksumani ihmiskuva oli suurelta osin valheellinen. Aloin siirtyä tieteellisempään, objektiivisempaan ihmiskuvaan.

Koin hyvin erikoisena näitä asioita koskevan tietynlaisen valikoivan vaikenemisen. Esimerkiksi Richard Dawkinsin kirjassa The Selfish Gene luonnosteltiin sukupuolten eriytymisen evolutiivista taustaa ja peliteoriaa: on edullista tehdä sukusoluja joissa on vähemmän resursseja, mutta jos molemmat osapuolet tarjoavat huonoresurssisia sukusoluja, jälkikasvua ei tule. Tästä seuraa kaikenlaista mielenkiintoista liittyen urosten ja naaraiden erilaisiin strategioihin ja sukupuolten fyysiseen erilaisuuteen, ja joka perehtyy asiaan pidemmälle tulee väistämättä siihen lopputulokseen, että miehillä ja naisilla todella on monenlaisia merkityksellisiä eroja. Jostain syystä Dawkinsin kirja kuitenkaan ei ollut mitään paheksuttua pseudotiedettä, vaan paljon puhuttua pop-tiedettä. Miten Helsingin Sanomien tiedesivu saattoi mainostaa kirjaa, joka johtaa ymmärrykseen sukupuolten eroista, samalla kun pääkirjoitus ja kolumnit kertoivat että koodaajista ja insinööreistä 50%:n pitäisi olla naisia ja että tietokonepelit tekevät pojista väkivaltaisia?

Samoin oli outoa havaita toisaalta älykkyyden keskeinen merkitys ihmis- ja yhteiskuntatieteissä ja toisaalta sen täydellinen mitätöiminen julkisessa keskusteluissa (“jokainen on eri tavalla älykäs”, “älykkyystestit mittaavat vain sitä miten hyvin menestyy älykkyystesteissä”), ja sitten vielä toisaalta ilakointi siitä että Bushia äänestäneissä osavaltioissa oli matala keskimääräinen älykkyysosamäärä. Viimeistään tässä vaiheessa menetin luottamukseni ja kunnioitukseni toimittajia kohtaan ammattikuntana.

Tutustuin myös näiden asioiden tiimoilta käytyihin kulttuurisotiin. Ihmisen biologiaa tutkineiden tai kommentoineiden joukossa oli paljon virkansa ja maineensa menettäneitä, marginalisoituja hahmoja. Jopa Lawrence Summers oli menettänyt paikkansa Harvardin johtajana kommentoituaan sukupuolieroja konferenssissa jonka tarkoitus oli puhua yliopistomaailman sukupuolieroista. (Sittemmin hän nousi uudelleen huipulle, ehkä siksi että hän oli edelleen paitsi huipputaloustieteilijä, myös demokraatti, ja hänestä tuli Obaman taloudellinen neuvonantaja.) Koin tämän kaiken epäoikeudenmukaisena ja tieteenvastaisena, ja perehdyin yhä enemmän siihen, mitä tältä väärinajattelijoiden puolelta löytyi. Tämän kehityskulun lopputulokset vaatisivat oman blogikirjoituksensa, mutta ymmärrän tänä päivänä että sellaiset sanat kuin “rasisti” ja “seksisti” koskevat myös minua, vaikka en niitä itsestäni käytäkään.

24-26

Aloin perehtyä vakavammin taloustieteeseen, ja erityisesti mikrotaloustieteen ymmärtäminen muutti monia poliittisia näkemyksiäni, tai pikemmin siirsi ne pois politiikan viitekehyksestä. Ehkä valistavimpia teoksia tällä saralla olivat Steven Landsburgin Price Theory and Applications (mikä tahansa vastaava oppikirja ajaa saman asian) sekä Frédéric Bastiatin esseet, joita jostain syystä pidetään Euroopassa naiiveina ja ei-vakavastiotettavina. Amerikassa niillä on edelleen hyvä maine.

(Olin aiemminkin tutustunut talousteoriaan kohtalaisesti sikäli, että osasin piirtää kysyntä- ja tarjouskäyriä ja päätellä niistä jotain, sekä tiesin mitä suhteellisella edulla tarkoitettiin, mutta syystä tai toisesta nämä asiat eivät silloin kypsyneet sen kummemmiksi yhteiskunnallisiksi oivalluksiksi.)

Liberalismini saavutti sellaisen vaiheen, että osallistuin Edistyspuolue-nimisen yhdistyksen kampanjaan kerätä 5000 kannatuskorttia jotta se olisi päässyt puoluerekisteriin. En ollut kovin optimistinen, ja kortteja ei saatukaan kokoon. Tulin siihen tulokseen, että sekä sosialismilla että klassisella liberalismilla on heikot mahdollisuudet menestyä politiikassa. Jälkeenpäin ajateltuna sekä Vihreiden että Perussuomalaisten nousu menestykseen ovat huikeita saavutuksia.

Lähimpänä libertarismia kävin ehkä luettuani Ayn Randin jälkeen (joka on erinomaista propagandaa ja emotionaalista vastamyrkkyä yleisvasemmistolaisuudelle) David Friedmanin kirjan The Machinery of Freedom, joka luonnostelee erilaisten valtiollisten järjestelmien korvaamista vapaaehtoisilla versioilla. Tuo kirja kannattaa lukea, ja se on erittäin ajatuksiaherättävä, mutta sen kokonaisvisio on sittenkin epärealistinen nykymaailmassa.

Tavallaan olin kokenut reaktiivisen heilahduksen sosialismista sen vastakohtaan, mutta ei se siltä tuntunut. Keskiössä oli edelleen oikeudenmukaisuus ja ihmisen vapaus toteuttaa itseään. Positiivisten vasemmistolaisten ilmiöiden suhteen toivoin, että niitä voisi perustaa vapaaehtoisuuteen, joka voisi toteutua vapaammassa yhteiskunnassa. Korostan: vapaammassa, ei täysin vapaassa. En missään vaiheessa ollut todellinen libertaari siinä mielessä, että olisin halunnut kaiken julkisen vallan purkamista (toisin kuin olin kommunistina toivonut kaiken yksityisomaisuuden sosialisointia), mutta alalla kuin alalla minusta näytti siltä, että oikea suunta oli se vapaampi. Oikeaa loppupäämäärää en osannut sanoa.

26-28

Aiemmin mainittu ihmiskuvan muutos alkoi kiteytyä, ja se johti myös lukemistani uuteen suuntaan. Taloustieteen ymmärtäminen oli saanut minut kysymään yhä harvemmin “Onko se oikein?” ja yhä useammin “Toimiiko se?”, ja ihmiskuvan muuttumisella oli nyt sama vaikutus. Koin konservatiivisen herätyksen. Tulin siihen tulokseen, että ihmisluonto on keskeisellä sijalla yhteiskunnan toiminnassa, ja vaikka ihmisluonto vaihtelee sekä paikassa että ajassa, sitä ei voi muovata kuin vahaa ideaaliyhteiskunnan tarpeisiin. Ihmiset ovat taipuvaisia luulemaan itsestään ja omasta järjenkäytöstään ja eettisyydestään liikoja. Rajoitusten ja kontrollin poistaminen johtaa yleensä huonoon käytökseen, niin eliitin kuin rahvaankin parissa. Ihmiset eivät yleensä pysty järjellään hallitsemaan harmonisesti edes omaa elämäänsä, ja yhteiskunnat ovat yhtä elämää vielä verrattomasti monimutkaisempia. Ajan kuluessa kuitenkin muodostuu jotain kestäviä rakenteita, ja näiden rakenteiden ylläpitäminen ja keinotekoinenkin ylistäminen ovat ainoita keinoja pitää pakka edes jotenkin koossa.

Yhteenveto suuresta aatteellisesta kaaresta voisi olla seuraava: nuorena katsoin ensin sisäänpäin, käytin introspektiota, pohdin oikeaa ja väärää, perehdyin teorioihin. Nyt katson sitä miten asiat ovat, yritän ymmärtää niitä menneisyytensä kautta, pohdin pieniä positiivisia muutoksia jotka eivät pilaa mitään, perehdyn historiaan.

Aloin sanoa itseäni konservatiiviksi, mutta ehkä minun ei pitäisi, sillä useimmissa poliittisissa kysymyksissä olen kuitenkin “liberaali”. Tämä on minulle hankala rako. Konservatismilla tarkoitetaan usein vanhojen rakenteiden ja erityisesti sovinnaisten tapojen ylläpitämistä keinolla millä hyvänsä – esimerkiksi kauppojen aukiolon rajoittaminen lain voimalla. Minulle pakkokeinot (= julkisen vallan käyttäminen) ovat vastenmielisiä ja niitä pitäisi lähtökohtaisesti välttää. Niihin liittyy merkittävä eettinen ja sosiaalinen kustannus, ja toisessa vaakakupissa täytyy olla merkittävä hyvä niitä perustelemassa.

Konservatismini on siis yksityistä, ja siinä on kyse siitä, millainen hyvä elämä tai hyvä yhteisö minun mielestäni on. Pakkokeinot ovat tarpeen, kun yhteiskunnan harmoninen ja rauhallinen elämä ja kehitys ovat uhattuina. Pakkokeinoja ovat minulle myös verojen kerääminen yhteisten menojen kattamiseen ja asevelvollisuus. Hyvinvointiyhteiskunta on stabiili, enkä halua pilata sitä, mutta suurempaa sosiaalivaltiota kuin tämän stabiiliuden luomiseen en kannata. Tässä mielessä olen oikeistokonservatiivi. Kannabiksen kriminalisaatiota ei mielestäni voi perustella oikein mitenkään – tässä mielessä olen liberaali. Suhtaudun huumeisiin varovaisesti henkilökohtaisella tasolla – tässä mielessä olen konservatiivinen.

Joskus näihin aikoihin lakkasin myös olemasta pasifisti.

Toinen tärkeä muutos, joka finalisoitui tänä aikana, oli suhteeni lasten tekemiseen. Olin aiemmin pitänyt lasten hankkimista suorastaan moraalisena vääryytenä liikakansoituksen takia. Kysyin mielessäni: miksi juuri minun pitäisi yrittää monistaa itseäni, mikä minussa on säilyttämisen arvoista, lapsiahan maailmassa riittää. Nyt tulin siihen tulokseen että jos en halua lapsia, se on kuin haluaisin maailman olevan tulevaisuudessa vähemmän sellainen kuin minä ja kaltaiseni. Kasvun rajat tulevat kyllä vastaan riippumatta siitä miten valitsen.

Ehkä itsetunnossanikin oli tapahtunut muutos, sillä nyt minusta oli selvää, että samoin kuin saatoin toivoa, että maailma olisi enemmän sellainen kuin ystäväni ovat (olinhan valinnut heidät ystävikseni), halusin itsekin jäädä geneettisesti ja memeettisesti maailmaan. En ole vain minä, vaan oma taustani, jonka hävittäminen maailmasta olisi tavallaan vastuutonta ja tappioksi. Päätin siis sittenkin haluavani lapsia ja aloin myös kannustaa ystäviäni perustamaan perheen. Tässä siis yhdistyi se, että näkemykseni ihmisistä oli tullut paljon biologisemmaksi (lapset muistuttavat yleensä vanhempiaan) ja se että näkemykseni itsestäni oli tullut myönteisemmäksi (halusin että tulevaisuuden ihmiskunnassa olisi mukana myös minun lapsiani).

Väläyksenä menneisyydestä mainittakoon keskustelu, jonka kävin ystäväni järjestämissä juhlissa tapaamani opiskelijan kanssa. Hän esitti, että länsimaiden hyvinvointi perustuu kehitysmaiden riistoon, ja minä olin eri mieltä. Todistelin, että kehitysmaiden resurssipohjaiset taloudet ovat kerta kaikkiaan arvoltaan niin pieniä, että kehittyneiden maiden valtavien talouksien pyörittämiseen ei niiden riistäminen voi mitenkään riittää, ja että jos kaikki taloudelliset suhteet näiden väliltä katkeaisivat, se olisi kriisi kehitysmaille vaan ei kehittyneille maille. Olin nyt sitä mieltä, että taloudessa on ennen kaikkea kyse korkeasta erikoistumisasteesta, tuottavuudesta ja kertyneestä ihmis- ja tuotantopääomasta, mutta vielä 5-6 vuotta sitten olisin voinut olla tuon opiskelijan asemassa.

Aloin viimein suhtautua kristinuskoonkin myönteisemmin, tosin todellinen usko on edelleen minulle vierasta. Usko näyttäisi olevan monille ihmisille luonnollinen, tärkeä ja hyödyllinen asia, ja kirkot ovat vastuussa paljosta hyvästä, eikä minulla ole näihin asioihin nokan koputtamista. Kun ennen seurasin uskon katoamista Euroopassa mielihyvällä, olen siitä nyt jopa hieman huolissani.

Nykysuunta

Tulevaisuutta on vaikea ennustaa, mutta jos muistutan ihmisten enemmistöä, nyt (30-vuotiaana) alan luutua ajattelussani näille sijoilleni. Liekin sammumista on havaittavissa. Olen alkanut suhtautua oikeastaan asiaan kuin asiaan myötätuntoisemmin ja ymmärtävämmin. Etenkin kahdenkeskisessä keskustelussa minun on vaikea tulistua kellekään nuoruuden tapaan. Näen poliitikkojen teot ja ihmisten mielipiteet heidän omien tilanteidensa valossa yleensä hyvin ymmärrettävinä, ja hyvyys ja pahuus ovat yhä enemmän asioita joiden kanssa jokainen kamppailee omassa elämässään kuin kokonaisten ihmisten attribuutteja. Tämä varmaankin johtuu osittain isäksi tulemisesta. Minulla on toki edelleen mielipide melkein kaikesta ja pidän ajattelemisesta.

Minua leimaa maalaisjärjen vähäisyys, vaikka aiemmin mainittu konservatiivinen herätys onkin sitä jonkin verran lisännyt. Olen aina ollut taipuvainen abstraktin ajattelun viemiseen pitkälle, ehkä liian pitkälle. On mahdollista, että liekin sammuminen ja ymmärtäväisyys tarkoittavat sitä, että ideologiset suojani ovat alhaalla, ja olenkin alttiina uudelle äkkivääryydelle. Minulla on joitain aavistuksia siitä, mitä tämä voisi tarkoittaa, mutta en halua avata sitä tässä sen tarkemmin. Itsensä tarkastelu “ulkopuolelta” on aavemaista; kun sitä tekee tarpeeksi pitkään, melkein mikä tahansa alkaa tuntua mahdolliselta.

Scott Alexander, tämän hetken kuuma nimi blogimaailmassa, kirjoitti äskettäin poliittisista erimielisyyksistä empatian näkökulmasta. Hän kertoi psykologista kehitysvaihetta mittaavasta kokeesta, jossa arvioidaan lapsen kykyä ymmärtää toisten maailmankuvaa. Kokeessa näytetään kahdelle lapselle laatikko, johon pannaan lelu. Tämän jälkeen toinen lapsista (A) viedään pois huoneesta, ja jäljelle jääneen lapsen (B) nähden vaihdetaan laatikossa ollut lelu toiseen. Toinen lapsi (A) tuodaan takaisin huoneeseen, ja huoneeseen jääneeltä lapselta (B) kysytään että mitä toinen lapsi (A) nyt luulee laatikossa olevan. Ennen tiettyä kehitysvaihetta lapset eivät ymmärrä että toisella on mielessä vain se, mitä hän itse näki, ja vastaavat että toinen lapsi (A) sanoisi laatikossa olevan se jälkimmäinen lelu.

Kaikki lapset oppivat tämän, mutta aikuisillekin on vaikea kunnolla sisäistää se, että toisilla on erilainen arvo- ja tunnemaailma. Facebook-keskusteluissa ihmisiä järkyttää toisten ilkeämielisyys ja alhaisuus, koska he sovittavat oman arvomaailmansa toisen ihmisen sanoihin ja tekoihin ja tuntevat että jos minä olisin tuollainen, tuntisin oloni iljettäväksi. Mutta toinen ihminen on toinen ihminen. Olen vasta aivan viime vuosina alkanut ymmärtää, mitä tämä tarkoittaa.

Narratiivinen kaari, minä ja muut

Seuraava lausahdus kuuluu panna tähän (jos en sitä itse tee, joku sanoo sen kommenteissa):

If you’re not a liberal when you’re 25, you have no heart. If you’re not a conservative by the time you’re 35, you have no brain.

(Tätä ei muuten sanonut Winston Churchill, mutta moni muu on sanonut jotain vastaavaa.)

Tämä on se ulkoinen kuva, jonka muut näkevät, ja jonka piikkiin muutokset on helppoa panna: “vanheni ja viisastui”. En voi kiistää, etteikö tuo klisee sopisi melko hyvin itseeni. Tie on kulkenut nuoresta vasemmistokiihkoilijaksi varhaisvanhaksi luonnekonservatiiviksi. Voin kuitenkin lohduttautua sillä, että ajatteluni on (omasta mielestäni) edelleen omintakeista ja “elävää”, enkä koe että olin nuorena tyhmä ja olen nyt tullut järkiini, tai että olen nyttemmin kovettanut sydämeni. Toisaalta tältä tuntuu varmaan kaikista muistakin.

On myös todettava, että vaikka tällainen kehitys on suorastaan stereotyyppi, lähipiirini ei ole yleensä ottaen tehnyt vastaavaa retkeä. Vasemmistolaiset ovat enimmäkseen pysyneet vasemmistolaisina ja oikeistolaiset oikeistolaisina, konservatiiviksi ei monikaan halua tunnustautua. Ehkä olen muodin edellä. Viime vuosina osa epäpoliittisimmista tapauksista on innostunut seksuaalivähemmistöjen asioista, antirasismista, feminismistä jne. ja liittynyt niiden ympärille muodostuneeseen nykyvasemmistolaisuuden piiriin. Pienempi osa taas vakuuttunut esimerkiksi Jussi Halla-ahon ennustuksista ja varoituksista ja tätä myötä tulleet “kansallismielisiksi” tai eurooppalaisiksi nationalisteiksi (tälle asialle ei ole vakiintunutta termiä, mutta ymmärrätte varmaan mitä tarkoitan).

Pidän enenevässä arvossa niitä, jotka edelleen ovat itsenäisiä vapaa-ajattelijoita – valitettavasti itsenäisyys tosin yleensä johtuu siitä, etteivät politiikka ja aatteet oikeasti kiinnosta, jolloin keskustelut jäävät pyörimään perustasolle.

Ehkä ideologisen kaaren kuuluukin olla nyt valmis, sillä olen nyt isä ja tiedostan miten vähän minulla itsenäisenä ihmisellä on merkitystä. Kun ajattelen poikaani, haluan korostaa hänen aatteellisessa kasvatuksessaan seuraavia asioita:

- Totuus ja tosiasiat ensin. On paljon parempi opettaa ajattelemaan ja tietämään kuin yrittää siirtää omia aatteita eteenpäin. Kärjistäen: lehdissä on joka päivä uudet uutiset ja aatteet, mutta matematiikka on ikuista.

- Sokraattinen metodi. Olen poikani ensimmäinen filosofian opettaja, ja siinä roolissa tehtäväni on kertoa ja kysyä, ei väittää.

- Avoimuus ja ymmärrys. Haluan opettaa ymmärtämään asioita toisten ihmisten näkökulmasta. Toivon että pojallani on parempi theory of mind kuin itselläni oli.

Kiitos kommentteja antaneille esilukijoille TK ja IS.